The problem with the new anonymous messaging app Sarahah isn’t that it creates a platform for cyberbullying (just walk away from your computer screen, jackass); it’s that it is playing a role in the leftist movement against free speech by ridding people of the responsibility of owning their words.

I don’t need to have used the app to know this. It’s obvious. In this time when social media is allowing for people to communicate less and less directly, making them more and more thin-skinned, careless with their speech, and, quite frankly, stupid, this app deals with the free speech problem by cleverly working around it. While most leftist social media platforms attempt to censor content or to simply suspend accounts when people say things that don’t conform to their collective beliefs, Sarahah allows the content to flow freely because no one in particular can claim responsibility for it. It is an anonymous free speech safe space, if you will.

Of course, the app knows who said what, so it allows you the option to anonymously block users if you get an undesirable message, so content can still be managed in that way.

Fair enough.

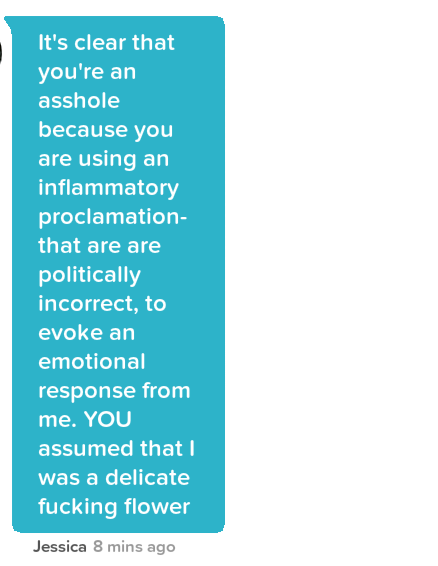

If someone messages you through the app telling you point-blank “you’re a dumb fuck”, you might not want to hear from that person again since they are lacking the tact and constructive criticism that the app would like of its users, and the same would be the case in real life, you can be sure.

The point I’d like to make in this post is that the Sarahah concept can seem all well and good on its own, but when you put it into a real world context, as with any new product, the users will determine its true identity. (this is through no clear fault of the creator; not every app developer knows enough about human nature to think through every scenario in which someone might use the app differently than he intended… this is why user feedback is so crucial). This post is my prophesy about why Sarahah’s identity will turn out more bad than good and why I would generally advise against using it.

Why Sarahah is Bad for Business

A good business provides a valuable service to the community. In order to ensure that the service continues to grow and improve, it is necessary that the employees work in an environment conducive to the free-exchange of ideas. That might make Sarahah seem like the perfect app, right? Actually, the contrary is true because of what the idea leaves out.

What is just as important as the idea itself is the employee’s taking credit for it. Sarahah doesn’t allow for this, neutralizing the dominance hierarchy within the company. The employer can reap the benefits of having the idea, but he does not have to give credit where it is due. This is convenient for the individuals at the top whose jobs won’t be threatened, and for the human resources department because they will have fewer cases to deal with, but it could hurt the company in the long run when their employees’ intellects are suppressed and promotions are given to the wrong people. This is bad news for female employees who, if they thought they were disadvantaged in the workplace before, will be even more so now, perhaps without their even realizing it. It is also bad for male employees who will inevitably lack the motivation to give any criticism at all.

Here are the differences between how women and men will be affected by Sarahah in the workplace.

Sarahah sneekily caters to the female temperament.

From a personality perspective, women tend on average to be higher than men in Big5 trait agreeableness. This means they are more compassionate, less assertive, tend to underestimate their abilities, and they don’t as often take credit for their achievements. They are also higher in trait neuroticism, which is sensitivity to negative emotion. This makes Sarahah the perfect place for women to speak their minds. They don’t have to give criticism directly, and they don’t have to claim fault if that criticism hurts someone’s feelings.

This might sound appealing to women, but I see it as taking advantage of the woman’s common workplace weaknesses. Though (probably) not intended, the inevitable consequence of this will be that even fewer women will stand out among their coworkers and be considered for promotions. They’ll be comforted now more than ever that simply sitting there and doing their jobs is enough, instead of taking the risks necessary to advance. (Of course, personality studies show that this is a good thing if they want to maximize their mate options, as women prefer mates who are at least as smart and successful as they are) All of this is true for some men as well, but I suspect men in general will encounter a different set of problems.

Sarahah Suppresses the Male Intellect

Since men are more assertive and aggressive, they will still be more likely than women to give criticism face-to-face, and there’s bad news for men who do. If a company begins to rely on Sarahah as the primary means by which to take criticism, then direct dialogue between people will be constricted, not enforced. Any man who does not use the app to speak his mind is taking a dangerous and unnecessary risk. He may get into trouble and risk losing his job if his speech is in violation of company policy. He won’t be able to play the traditional, competitive, risk-reward game that is crucial to his potential to climb the company ladder.

Challenging the status quo is an important way in which men typically show their ability to think critically, articulate, and negotiate – skills that are necessary for managing a good business at all levels. Sarahah suppresses these skills. This will allow HR to keep the hiring process neutralized, so they do not have to promote people within the company based on merit, but rather by whichever absurd and counterproductive standards they choose (e.g. to meet notoriously anglophobic ethnic diversity quotas).

Why Sarahah is Bad for Personal Relations (to point out the obvious)

It might sound appealing to find out what your friends and acquaintances really think of you, but I suspect that the anxiety that will result from not knowing who exactly said those things will far outweigh any positive effect that the criticism may have on you. Imagine walking around at a party where all of your closest friends are present, knowing that half, maybe even all of them have only been able to honestly open up to you anonymously.

A good friendship or relationship should not only be conducive to, but founded on open, honest communication. I know it sounds cliché, but this cannot be overstated given that Sarahah exists to deny that. In fact, we identify who our friends are based on how open our communication is with them, do we not?

Consider this… your primary or best friends are those few who you can be absolutely open with. You know who they are. Your secondary friends encompass a wider circle. They are people you may call on regularly, but the subject matter of your communication with them is limited, whether to specific topics or to a level of depth in general. Your acquaintances are everyone else you know – people you could (and often should) do without.

Which friend group do you suspect is the most likely to send you overly-critical messages on Sarahah? Acquaintances? The people who know you the least?

Hmm, maybe not.

Acquaintances might be the most likely to send you the occasional “you’re a dumb fuck” sort of message. But, since they know you the least, they think of you the least. They care for you the least. They’re the least likely to try to help you. So, I’d guess not.

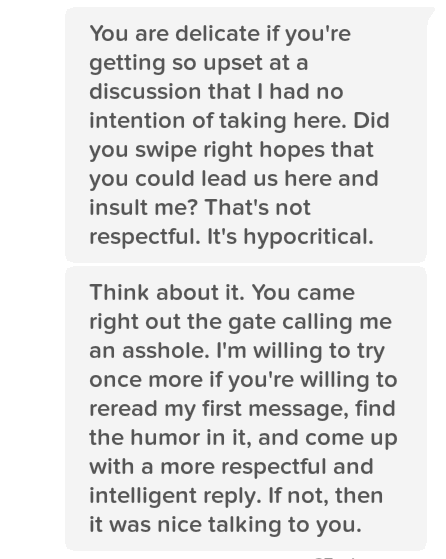

What about those best friends who use the app? They very well may use it to give you some much-needed advice, but who are they? Though the advice is sound, are they really your friends if they can’t sit you down and talk to you?

You might be disappointed (or even relieved, if you’re a particularly strong person) to find out that some people who you thought were your best friends are really secondary friends, or mere acquaintances, or just snakes and not your friends at all. In fact, any “best friend” who might use the app out of fear of being honest with you, no matter the content of their message, is doing you a huge disservice. They’re simply acting cowardly.

Conclusion: Don’t Be a Pussy

Don’t use Sarahah. Own your words. Be an open, honest, and responsible human, for your sake and the sake of your friends and coworkers. If your company tries to adopt Sarahah in order to take criticism, explain to them the problems that would cause for you and for them. If they insist, then give criticism directly anyway. Get into a fight with those dumb cunts in HR. Get fired. Chances are that it’s not your dream job anyway.

If your friends announce on social media that they just started a Sarahah account, they’re reaching out for help. Take them out for a drink and ask them what’s up. It may require a bit of persistence, but if they’re really your friend, then it will be worth it.

Despite the difficulties in the short-term, the long-term benefits of having straightforward, critical discussions with people will be worth it. You’ll show them that you are worth it, and they will reward you for it. But, of course, don’t do it for the reward; as with anything, do it simply because it’s right.