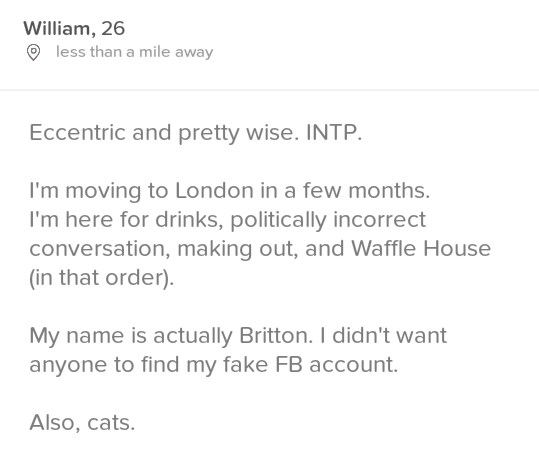

I’m Britton, as you should know, and below you’ll find the bio I wrote for my Tinder profile. If you don’t know what Tinder is, then get your head out of the sand, and read about it here.

I was in New Orleans the other day, getting my swipe on, and then I came across this fine, older lady.

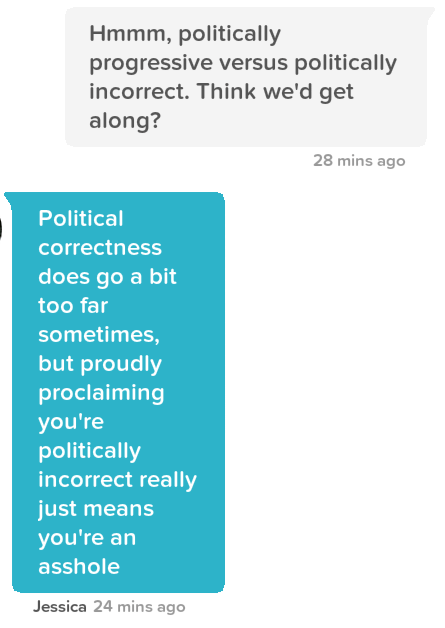

The first things, ‘politically progressive’ and “the f-word”, I admit, probably should have raised red flags before even her shitty taste in music did. Those terms on their own hint at far-left political views, but the two of them together scream ‘SJW‘. However, she was hot, and that’s very rare of feminists, so I read into her words and saw deeper possibilities. I was hoping that maybe we could talk some philosophy, giving her the benefit of the doubt that her knowledge on that subject wasn’t confined to new-wave feminist crap. Hey, maybe she was even a feminist of the second-wave, non-radical kind, and ‘progressive’ just meant that she was kind of liberal and open to reasonable and necessary change. Maybe she’d even have a cat named Elvira. With this optimistic attitude, I swiped right and immediately tested her humor to see how “open” she really was.

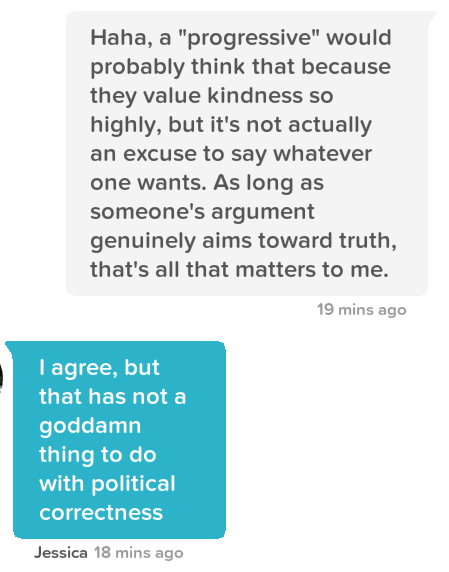

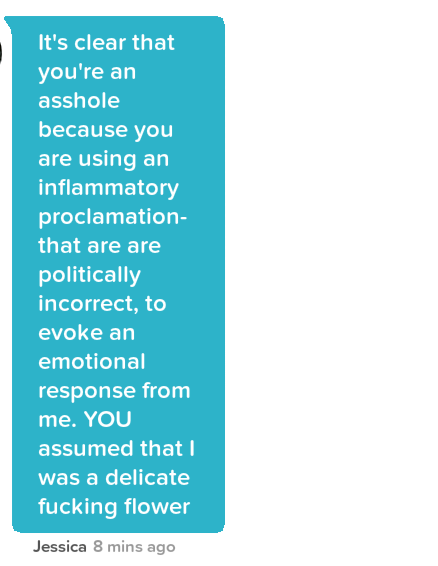

BOOM! No fun or games with this one. Did I “proudly proclaim” that I am politically incorrect? Reread my bio, and let me know. I think I’m just straightforward about what I want out of my Tinder experience. She could have easily swiped me left if my intentions didn’t line up with hers. Looking back, though, maybe I should have ended my first message with a winky face. 😉

Do you value truth, Jessica? DO YOU? We’ll find out. Also, Jessica, I’ll be addressing you directly from here on. Wait, is it ok that I call you by your name, or would you prefer something else? I don’t want to be too incorrect and risk “invalidating your existence“.

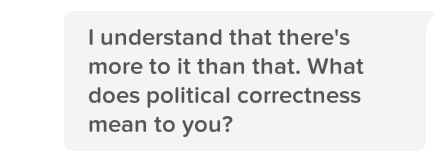

Yeah, let’s define a term together! That sounds like a fun philosophical exercise. Maybe you’ll even return the favor by asking me how I would define the term, and then we’ll find some common ground, bettering both of our conceptions of the world. Learning stuff is fun! You read philosophy, so you agree, right?

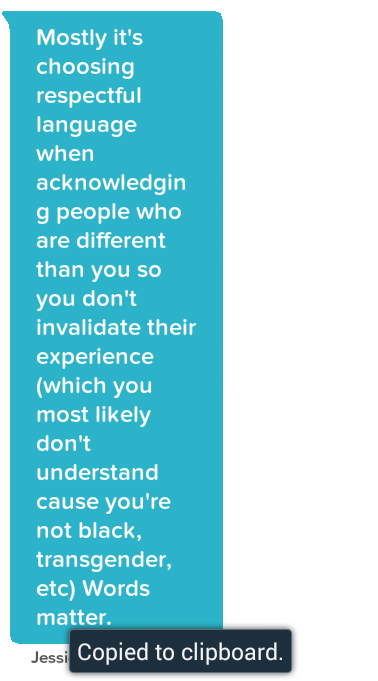

Annnnnd there it is. You pretty much nailed it, Jessica. I’m guilty of whiteness, so there’s no need to ask me what I think ‘political correctness’ means. Your understanding of how language works, on the other hand, seems a bit strange, and the philosophy you read may be of questionable quality. My validity on that topic comes from my education in linguistics and philosophy of language. But, you’re attempting to “invalidate” me because I’m… white? Hmmm.

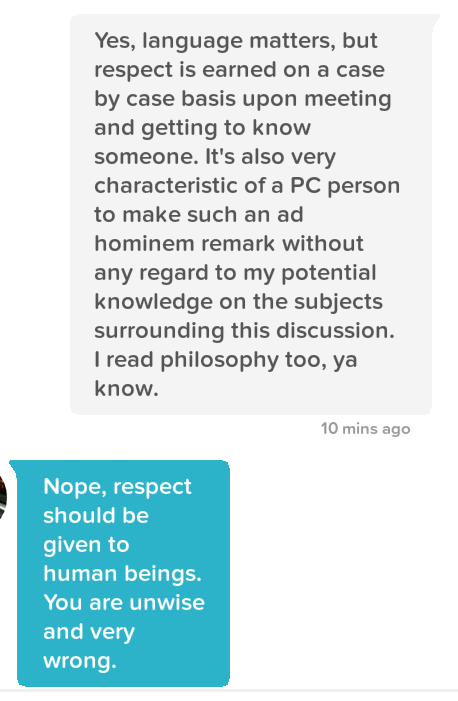

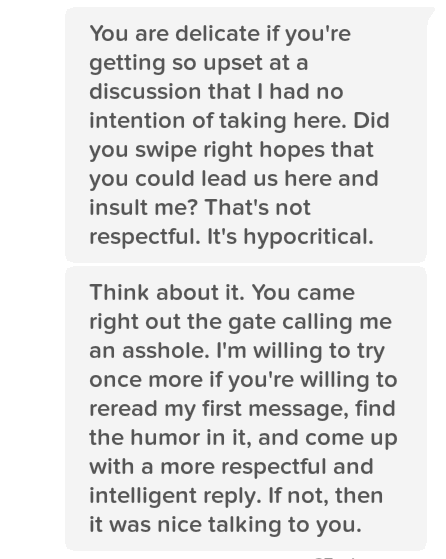

I don’t think that speech is an activity so consciously aimed toward respect, nor do I think it’s a good idea to blindly respect people at all. In fact, it’s dangerous. I’ll spare you the technical linguistic part of the argument because I’m starting to sense that you have a screw or two loose, but I still must address the respect-issue.

Also, how are you so sure that I’m not black or transgender? If you respected me, then you would have asked about my preferred identity because race and gender are determined whimsically and have no biological basis, correct? No, you should have simply requested a dick pic, Jessica. Truth requires evidence, and I have plenty of it.

So, maybe there’s more to political correctness than your definition, Jessica, and maybe I know some stuff that you don’t. Maybe you’d be interested in hearing it. Maybe if you weren’t so keen on blindly respecting others, then you wouldn’t be so liable to get mugged and raped in a dark alley in New Orleans. Or, maybe you’d like that because you’d become a martyr for your ideology. At this point, you’re not giving me any reason at all to respect you, but I do fear for your safety. After all, you’re right that the world isn’t a very kind place.

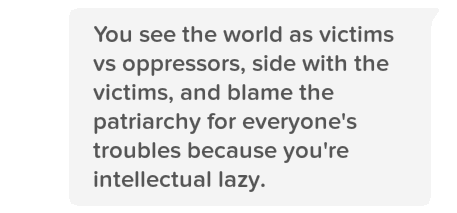

I figured I’d play the “patriarchy” card since you already accused me of being part of it by virtue of my straightness, whiteness, and maleness. What did you expect? Why did you swipe me right if you hate me by default, unless you wanted to hate-fuck me (shit, I may have missed my shot)? I mean, you’ve seen my pictures. Chances are that I’m not black under my clothes. In fact, I’m even WHITER there. Well, actually, there is a very small part of me that is kind of tan.

*ignores grammatical errors and moves on*

I know I’m an asshole, Jessica. There is no need to repeat yourself. But, does being an asshole make me wrong? No, Jessica, you’re the meanie who committed ad hominem. I also didn’t appeal to emotion to argue my point. You just took it that way. Taking offense and giving it are NOT the same thing. That’s Philosophy 101.

But…do save me! Please save me from my problematic ways so I can be more compassionate like you and make the world a more progressive place! Or, do I need a degree in women’s studies to be infected with your profound wisdom? If it’s LSU that infected you, then you’re right that there is no hope for me because I dropped out of that poor excuse for a higher-education institution after just one semester of grad school.

On the other hand, I could help you by revealing your greatest contradiction, and maybe even give you one more chance to get laid by me, knowing well that so few men would have gotten even this far with you. I mean, this is Tinder. Why else would you be here? Yeah, that’s what I’ll do because I want some too. I’ve learned to accept that liking sex makes women delicate flowers and men oppressive misogynists. It’s cool, really, I don’t need to be reeducated. I’ll even let you play the role of misogynist, and I’ll be the victim, and you can oppress deez nuts all you want.

That’s where it ended. So…

What the hell is going on here?

I don’t think that I need to go into detail about what is going on here. There are plenty people who have done that very well already. For example, Dr. Jordan B. Peterson in this brilliant snippet from the most popular podcast in the world. The general point I want to make is that we are in a strange place where people like Jessica are multiplying exponentially by the semester, thanks to politically correct ideology infecting universities, business administrations, legislature, and now even Tinder (as if Tinder doesn’t already have enough spam)! This is the time for talented and capable people, mostly men, to stop ceding power to the people who live in those boxes; they’re wrong, and they’ve snuck their way into power without truly earning it. To stand up for truth is to stand up for yourself. However painful that may be now, it is absolutely necessary for the survival of our species. After all, if we were all angry, 35-year-old feminist virgins, of course humanity would end.

Since we aren’t all like Jessica, one day we will be without these people completely. Let’s give them what they want: spare their feelings, thus depriving them of the open, truth-seeking dialogue that would mold them into stronger moral beings and free them from the narrow and suffocating constraints of the feminist ideology. Since they aren’t open to that sort of thing, they will eventually self-extinguish under their childless philosophy and rot in the miserable hell that they’ve created for themselves.