To continue from my previous post, self-governance is not as common as we’d like to think, but I intend to hold that it is still possible for everyone in certain cases and following a degree of conscious effort to understand the self. That said, it seems plausible that it is not a function of most of us, most of the time.

Although there are many, I want to focus on three sources of self-governance from which we can draw principles for living, as I mentioned at the end of the last section. They can be from morality (truth), from self-enforced boundaries (the self), or from external authority (others).

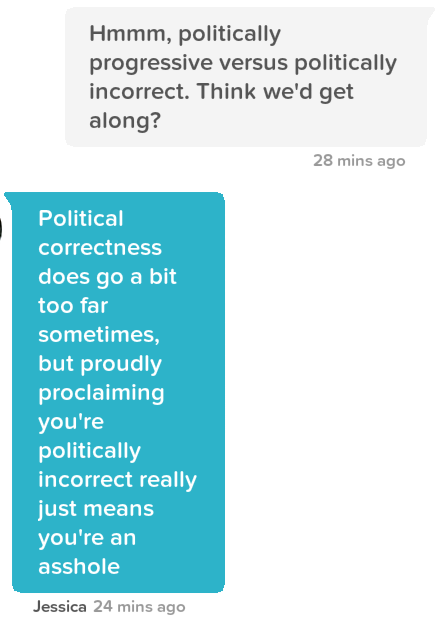

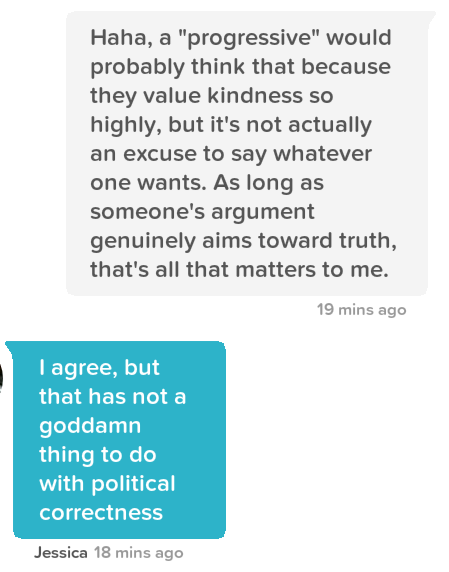

Appealing to external authority for the formulation of principles, regardless of how true they are or how good the results they produce, is a logical fallacy — i.e. an error in reasoning. Whether they are copy and pasted from your father, mentor, religion, or boss, nothing is true or good because of the person’s position of authority, and you give up your own inner authority by blindly following that of another. People have varying degrees of just authority, and such a degree may represent their ability to guide someone toward the truth if it is indeed the truth for which they live — this means that they have good intentions. Good intention is unconditional and does not seek money or control, and it is only from those with good intention that we can truly learn anything. Still, lead us they need not. Their wisdom should merely help us to guide ourselves. It could, on the other hand, be that the authority is merely self-serving (as is the case for leaders for whom pride is the driving force of their reign), and one’s ability or inability to distinguish between others’ true or ill intentions means that one is vulnerable to selling their soul’s autonomy to the ones who seek it. External authority is never the answer for principle-setting.

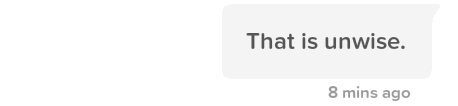

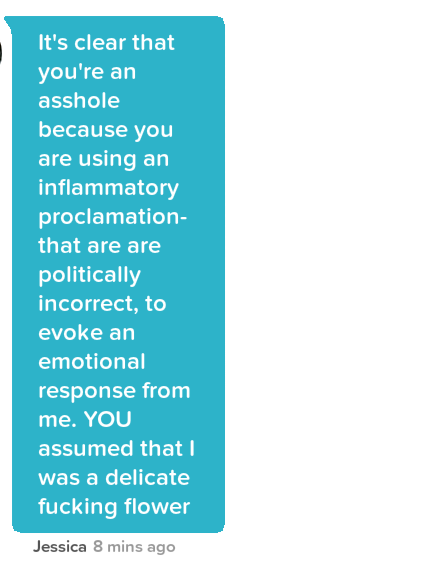

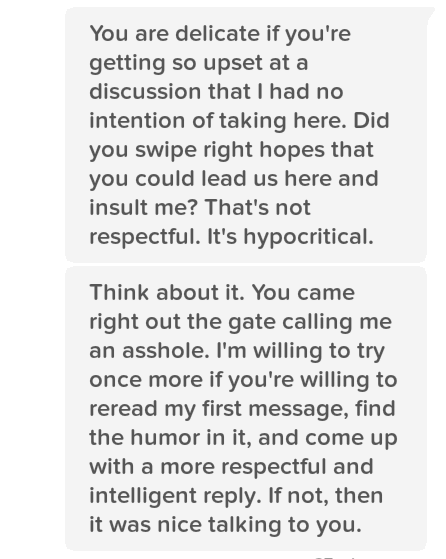

Self-enforced boundaries come merely from the self. They are often overcorrective, flight response limits to external stimuli and events. So, although one is the sole, conscious arbiter of these rules, they are at the willing hand of the world, and so boundaries are not set with clear consciousness. They draw a line in the sand and say “I will do that and not do this”, regardless of the circumstances, thereby, paradoxically, letting circumstances control their rigid minds. They shortcut the work one must do in order to adapt to external circumstances as to “do right” under any conditions, which requires cultivating a filter for what one will allow oneself to be influenced by. Boundaries, rather, build a wall against facing circumstances as they are. They mistake defensiveness for genuine protection, and they only delay the cultivation of character.

The human mind, much like the body, is anti-fragile. The more one is exposed to and observant of something, the more one understands its patterns, and the less one fears it. Boundaries do not seek to understand things in themselves, but rather, avoid those things from fear. However, this type of self-governance is a step in the right direction for someone who was previously guided more directly by external authority.

Genuine moral principles, in contrast, constantly, voluntarily take on the challenge of being tested. It is as if one’s belief system is in a constant state of exposure therapy. With every test, a principle gets stronger because it is both being exposed to its foe and making use of the wisdom gained from facing all of the tests from the past. Expose yourself to nothing, and you will go weak. Principle must come from self-awareness, but not arrogance, and understand that the external world is not within one’s control. Therefore, minor improvements occur in one’s principles over time. A principle-forming person knows that the only thing he can control is his responses to externals, based on his patterned understanding of those externals and how he is both a keen observer and a dutiful participant in all of reality. This type of person is a spiritual person who has gratitude for life and all of its struggles and joys, and they relish the duties of observation and self-improvement. This path implies a belief in some universal conception of truth and goodness, and self-improvement equates to the process of sharpening one’s perception as to orient them closer to that universal state with every thought, word, and action.

Self-governance from the cultivation of moral principles is a path rooted in unconditional acceptance — unlike boundaries which are seen as good under the condition that they don’t cause one pain, or external authority which has no intrinsic right to speak on others’ behalves to begin with — and they are the only governance pattern whose origin really is in truth and goodness for one and for all. “Truth and goodness for one and for all” is perhaps the core value from which any sustainable principles originate, for it is universal and non-polar in nature, which relinquishes the ego’s need to believe and prove things…

As it turns out, the ego rules most, and those people would rather take the easy path of outsourcing their own moral authority anyway.