On the 10th of July, 2017, I had the pleasure of attending a talk on American Impressionism at the American Museum of Western Art in Denver, Colorado, and to view their impressive (pun intended) Anschutz Collection of works. The experience gave me much to think about, including but not limited to the differences between American and French Impressionism, both in terms of style and purpose, and how impressionism uniquely fulfills the purpose of art more generally. As a philosophizer with an interest in aesthetics, rather than as an artist, I naturally am more inclined to discuss purpose than I am style and technique, though those things are not mutually exclusive.

On the Critique of Art

It is an interesting thing that philosophers do in discussing meaning and purpose of art. One symptom of this activity is that we often take for granted the technical skill of the artist in favor of a work’s meaning or lack thereof. We take for granted that the artist is satisfied with the degree to which he has shown what he intended to. We take art as a top-down process, while for the artist, it is a bottom-up process. For this reason, we hold art to a very high standard, and that puts pressure on the artist to show us something true, assuming, often falsely, that they are trying to show anything at all. Perhaps we should show more gratitude to the artist in this regard, for the technique is the necessary tool, usually cultivated over many a year, through which the artist expresses what is dear to us or, at the very least, to them. That is the disclaimer I would like to preface with before I go on philosophizing. I am not a visual artist myself, and I do admire those who are proficient in that medium, even if they do so with no or poor intention.

Anyway, and on that note, whether the artist says what he attempts to sufficiently is its own matter, so we should approach our critique gingerly, as to see through any such shortcomings. We simply want to understand the message that lies beneath. It is the same in music, where if one really listens, the technical quality of the recording doesn’t matter. The content’s form is what matters, for it inspires the function, and intentional functions merely serve the form, as Roger Scruton shows in his BBC documentary. Very often the artist is not able to communicate his ideas in any way other than through his brush or instrument. Clearly, though, he somehow understands what he is doing. He is like a scientist of meaning in this regard, as science is a bottom-up process for the scientist who hopes (naively) that truth will emerge from the compilation of facts, but it is also a top-down object of criticism for the philosopher.

Is this not fair, however? Does the purpose not precede the style of the work? I think any informed critic should agree that it does. To agree, one must understand what art does, generally speaking. That is to reveal something true about reality or human nature which is normally hidden, suppressed, or taken for granted. It shows us something that we as individuals or as a society need to pay more attention to. Even if that message is to show that beauty can exist in isolation and complexity, I think this point still stands.

There is also the purpose of much contemporary work which is to “be the best it can be for the sake of itself”. This purpose may, though not always, neglect the objective standard by which we might judge art (insofar as we might consider symbolic truths about reality and human nature to be objective), and it rather qualifies art according to the power of human creativity, even if the product of that creativity lacks an organized structure toward a higher purpose.

This approach to judging art is a postmodern one: here are no universal standards for anything, quality is merely relative, and meaning may be interpreted in an unlimited number of different, subjective ways with no one way being more accurate than any other. We take the human creation to be larger than the reality that gave birth to it and that permanently contains it. This is a mistake of the ego-mind. Postmodern pseudo-intellectuals (e.g. most French philosophers of the 20th century, the scientismists of today, such as Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris) make with human rationality. They worship rationality as their God and fall in love with its creations no matter how disorganized they may be, all at the expense of what the work might be trying to tell us. What postmodern art, literature, philosophy, and even science are trying to tell us, in the rare occasion that they are trying to tell us anything at all, is in fact false. Even when it does land on something true, it is by coincidence because truth was never the intention to begin with.

Does Impressionism Fulfill the Purpose of Art?

What I like about impressionism, whether French, American, or otherwise, is how subjectively true it is. One could say, in other words, that it is authentic. A good impressionist painter is skilled enough to get their message across, and it is one which only that particular artist can convey. Nevertheless, it tends to be digestible to anyone while maintaining its individuality.

Is this not the dream of the west? In its high form, western ideals, particularly in America, allow one to be one’s own authority for what is good. This can, of course, be taken too far — as to put the search for “my truth” ahead of what is the truth, but this is not the overall intention of genuine liberty. It is more a matter of not letting the how deter one from the what one decides will fulfill one — and more deeply, that the what is founded on a why that we all agree is for the good in a just society. We all have different stylistic expressions of doing what we do, but there is an underlying law of reason that maintains that our individual efforts have some universal truth and benefit.

Contemporary, abstract art has no distinct subject matter, and it therefore leaves us to question whether the overall viewpoint which represents it is valid. It is, rather, an abstract perspective on an equally or more abstract subject. If the picture which the art represents is not real, then what is the representation (the art itself) worth? This probably-not-real-and-definitely-not-meaningful style of art is the perfect accompaniment to the aforementioned political and cultural climate in the west, which opposes the ideals of free expression of ancient truth on which the United States Constitution is founded, for example (supporters of this type of art, unsurprisingly, claim that beauty is subjective and are actively trying to destroy traditional values in education and politics). It values “my truth” over the truth, and in convincing the collective ego that “my truth” is a worthwhile pursuit, it tears people further away from meaning, leaving them as weak, powerless, and confused as an otherwise perfectly rational person observing Duchamp’s “Fountain” (it’s just a urinal) would be. Contemporary art is a movement representing the fear of and disregard for beauty, ancient wisdom, and one’s own individual authority. Both nature per se and

life-sustaining expressions of sexuality, as countless specific examples would show in the style’s erotic manifestations, are portrayed as unimportant or nonexistent. In this movement, nothing is sacred.

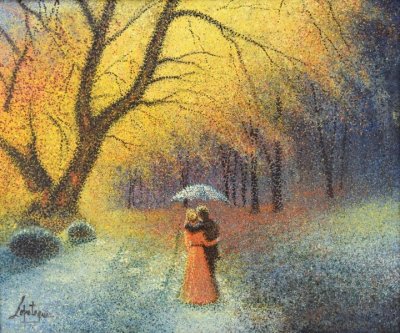

Impressionism, more gracefully, is the style of visual art, painting in particular, which contains infinitely variable impressions of things which we all know are of value beyond our selfish ends. The subject matter — nature and our relationship to it, from landscapes to lovers — maintains its sacredness and is

conveyed in a style that is especially unique. It is an abstract perspective on a concrete picture of reality, we could say. American impressionism, overall, is an easily-perceived yet highly creative expression of the many great, natural wonders of the American countryside and ways of life — i.e. the foundation on which freedom of expression itself is held as the paramount liberty, and where “trust in God (or truth itself)” is the default principle. In my travels outside of the United States, for example I have been complimented on my strong sense of self and belief that things will unfold as they should, which those people have attributed to my “American-ness”, rightly or wrongly.

Conclusion: Is American Impressionism Superior?

…to other contemporary styles of art? It seems so. By a classical measure, American Impressionism is good because of its return to classical subjects such as nature and love, and its attempt to convey awe for their beauty, rather than to bastardize it. It holds weight by creative measures as well for its uniquely subjective approach in doing so. However, if you enjoy chaos for its own sake, you are well within your rights to prefer contemporary abstract and absurdist art forms (I’m not talking down on Eric Andre — comedy is a unique case. See my MA thesis). The difference between preference and goodness is another issue. In general, it is permitted in the west that we can have disagreements about these kinds of topics and still function, yet that the cream will still rise to the surface, and that in extreme cases, it is worth fighting for. I wouldn’t consider one impressionist seeing a landscape one way and another seeing it another way as a pressing disagreement, but rather that some people can accept what is true and good for one and for all in their own way, and others are free to reject it at their own peril, also in their own way (have fun with that).

All art movements represent something about the values of the culture from which they emerge, and it does seem that there are at least two art movements going on right now, corresponding to the two general views on life. There is the ilk of culture that glorifies what opposes traditional conceptions of beauty and, therefore, sustainable ways of life — both through art and by flaunting their mutilated bodies in the street — and these are the “progressive” folk who align their aesthetic preferences with the shock and hedonism of contemporary abstractism. Then there are those who see that we have indeed inherited some values and structures that are worth holding onto, and that true power of both individual and collective thriving requires that we agree on some foundation of abstract-yet-observable conceptions of what is true, good, and beautiful. American Impressionism, insofar as I can tell, is making a real effort to acknowledge this foundation while leaving more than enough room for individual expression. American Impressionism: universal good, subjectively understood — just like the us.